Inclusion is a concept in education most often associated with minority groups and people who experience disability, but in fact, inclusion is about everyone. Inclusion is a human right (Declaration on the Rights of Disabled Persons 1975) a legal entitlement to all (Commonwealth Disability Discrimination Act 1992) and a core pillar of educational policy (Disability Standards for Education 2005).

“Inclusive education means that all students are welcomed by their school in age-appropriate settings and are supported to learn, contribute and participate in all aspects of school. Inclusive education is about how schools are developed and designed, including classrooms, programmes and activities so that all students learn and participate together” (DET 2015, p 2)

The following guiding principles, based on the Australian Disability Standards for Education (2005), underpin the Australian government’s guidance on planning personalised learning and support in schools:

- All students can learn

- Every child has a right to a high-quality education

- Effective teachers provide engaging and rigorous learning experiences for all students

- A safe and stimulating environment is integral to enabling students to explore and build on their talents and achieve relevant learning outcomes

- For students with disability and additional learning needs, reasonable adjustments should be made where required (DET 2015, p. 3).

The priority of inclusion for all children is also explicit in the Australian Professional Standards for Teachers across a number of focus areas, in particular: 1.5 Differentiate teaching to meet the specific learning needs of students across the full range of abilities; 1.6 Strategies to support full participation of students with disability; and 4.1 Support student participation (AITSL 2011).

The Australian Curriculum is an inclusive curriculum for all students:

Students with disability are entitled to rigorous, relevant and engaging learning opportunities drawn from age equivalent Australian Curriculum content on the same basis as students without disability (ACARA 2016).

Across Australia, states, territories and systems interpret and apply inclusive practices through the lens of their own curriculum, planning and reporting processes. At the national level, the annual Nationally Consistent Collection of Data on School Students with Disability (NCCD 2020a) collects information about Australian school students who receive an adjustment to address disability. This data collection takes a strengths-based approach to supporting resource allocation for students with disability.

The Disability Standards for Education require that all Australian schools:

- ensure that students with disability are able to access and participate in education on the same basis as students without disability

- make or provide 'reasonable adjustments' for students where necessary to enable their access and participation

- provide reasonable adjustments in consultation with the student and/or their associates; for most students, this means their parents, guardians or carers.

Meeting legislative requirements

A handy one pager that outlines the key role teachers play in supporting Disability Standards

The NCCD asks schools to consider the needs of their students and to collect evidence of the level of adjustments they make to provide for their students’ needs, as well as providing information about the broad categories of students’ disabilities (physical, cognitive, sensory or social/emotional). This allows schools to better plan for and support teachers across the school to personalise learning for their students. Since 2018 the NCCD has helped the Australian Government distribute funding by using these data to inform the disability loading provided to schools.

According to the NCCD nearly one in five (19.9 per cent) school students across Australia received an adjustment due to disability in 2019 (DESE 2020). As such, it is clear that inclusive education and supporting students with disability in schools and classrooms is a priority for all educators in Australia. Students with disability are taught in a variety of contexts depending on the best interests of the student to ensure they can participate in a range of educational opportunities - specialist schools, specialist classes/units in mainstream schools and within mainstream classes in mainstream schools (Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability 2020). This Spotlight summarises principles of inclusion and the responsibilities of Australian teachers and school leaders in supporting full participation of students with disability in their schools. Rather than discussing specific types of disability, the focus in this Spotlight is on broad strategies aimed at meeting all students’ learning needs.

Data on disability

The Disability Standards for Education 2005 includes seven criteria, ranging from “total or partial loss of a part of the body”, to “a disorder, illness or disease that affects the person's thought processes, perception of reality, emotions or judgement, or that results in disturbed behaviour” (p. 9).

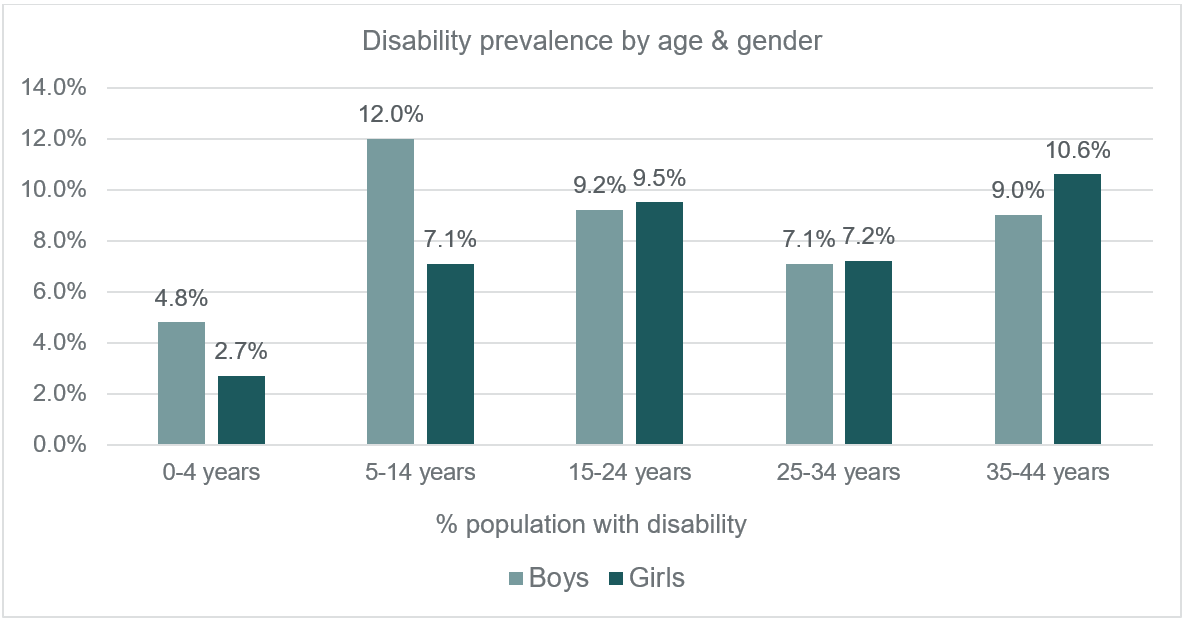

In 2018, 7.7% of children under 15 were reported as having a disability, an increase from 6.9% in 2012 (ABS, 2019). The proportion of people living with a disability increases rapidly after the age of 45, although the incidence of autism and other specific types of disability declines (ABS, 2019). Fluctuations in the prevalence of people with disability occurs from childhood to middle age (Figure 1).

The prevalence of disability in babies, toddlers and pre-schoolers (0-4 years old) is lowest of all ages at 3.7%. The proportion increases to 9.6% in school-aged children (5-14 years old) (ABS, 2019). There is a large gender difference in the school aged children, with 12% of boys and 7.1% of girls reported as having a disability (Figure 1). It is not clear the extent to which this sex difference reflects a social bias leading to increased likelihood of boys being diagnosed, or if there are sex-based differences in genetic susceptibility to neurodevelopmental disorders (Nowak & Jacquemont 2020).

Figure 1: Disability prevalence by age group 0 – 44 years, 2018. Data source: Survey of Disability, Ageing and Carers: Summary of Findings (ABS 2019)

Around one in twenty-two (4.5%) of children in Australia have an intellectual disability, other common types of disability effecting school children are sensory and speech disabilities (3.1%), psychosocial (2.7%), and physical (1.8%) (ABS, 2019). Of children with a disability who attend school, 86% attend mainstream schools, and of these 19% attend special classes within a mainstream school (AIHW 2019).

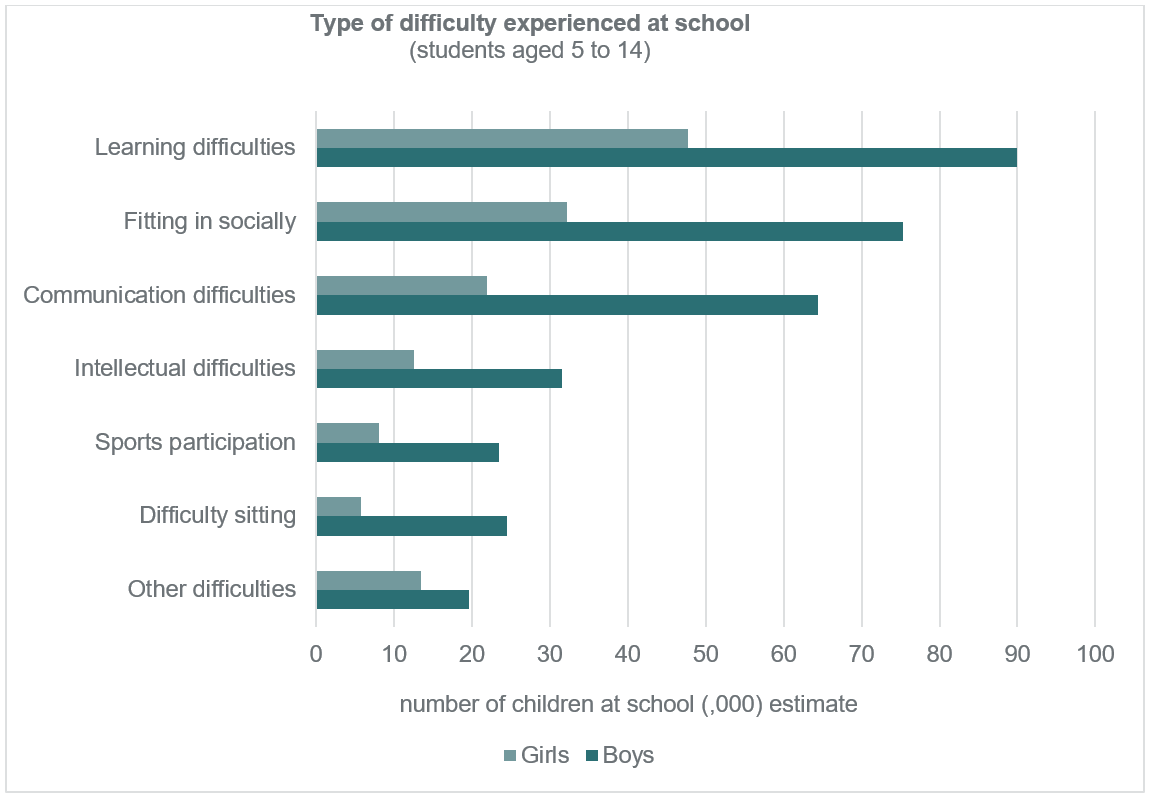

The most common type of difficulty students with disability face at school is learning difficulties (47,000 girls and 90,000 boys), followed by fitting in socially (32,000 girls, 75,000 boys) and communication difficulties (22,000 girls, 64,000 boys). Other difficulties, intellectual difficulties, difficulty in sports participation and difficulty sitting are also experienced by many students with disabilities (ranging from 6,000 to 24,500 students) (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Type of difficulty experienced at school. Data source: Survey of Disability Ageing and Carers: Children with Disability. Table 8.1: Children aged 5-14 years with disability, living in households and attending school, Schooling restriction status, type of difficulty experienced 2018 (ABS 2019)

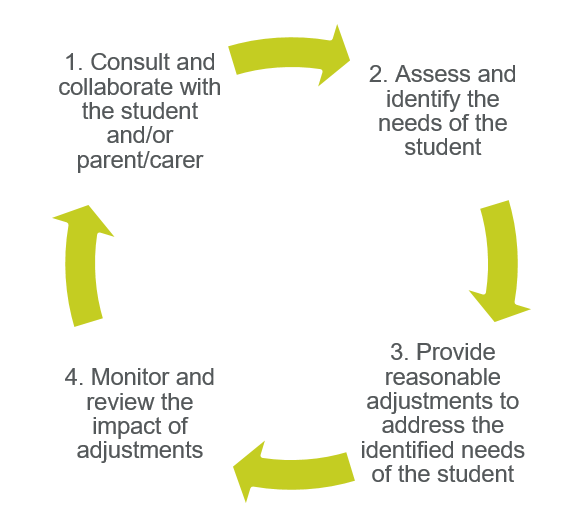

The goal of inclusion is to develop processes of personalised learning and support so that students with disabilities can engage in learning and schooling in the same way as their age-peers. The following four-step process is a guide for developing personalised learning and support.

Figure 3: Personalised learning and support (NCCD 2020b)

1. Consult and collaborate

Getting to know their students is a key goal for teachers, one that involves discovering students’ backgrounds, strengths, interests and goals. When teaching a student with a disability, this is a collaborative venture requiring close consultation with students, their family, and often a wider support team. Establishing and maintaining the best support for the student is a role shared by the class teacher and their school leader.

A Student Support Group (SSG) is ‘the team around the student’, which may consist of the students’ parents/caregivers, their teacher and the teacher’s aide/s, a school leader or coordinator responsible for students with additional needs across the school. Any allied health professionals who have a therapeutic relationship with the student could also be included, as well as the student themselves where their communication needs and maturity allow it. This group may meet regularly to discuss the needs of the student as they evolve over the course of their education, including needs and learning goals – a personalised plan resulting from these discussions may then be reviewed regularly. Student support group meetings are usually initiated by the school although parents are also able to instigate these meetings whenever there are changes in a student’s needs that are likely to impact their learning. The SSG may be named differently depending on the jurisdiction within Australia.

2. Assess and identify the needs of the student

Though teachers are neither qualified nor expected to diagnose disability, they are in a position to recognise a student who is not learning as expected, and to discuss their observations with school leaders and the student’s family. In most cases, students with disabilities will require assessment by a paediatrician and/or allied health professional (psychologist, physiotherapist, specialist educator, or speech or occupational therapist) to support identification of their disability. Where a student’s learning needs were picked up by parents, maternal child health nurses and early childhood educators prior to schooling, such assessments may have already been completed. If the student receives support through the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS), schools and families may share some of the information from that assessment to determine the student’s needs at school.

Historically, the language of school-based processes has tended to focus on students’ deficits and encouraged parents/carers and teachers to problematise students’ needs (Mitchell 2015). The introduction of the NCCD and more inclusive practices has encouraged a shift towards assessment of student needs in terms of the curriculum. In order to assess student educational needs in a consistent way, some states provide a specific assessment system that is formative in nature and directly informs the teaching of students with additional needs. For students transitioning to Foundation[1], their learning needs may be identified through diagnostic assessments[2] given to all students. Other assessment strategies can also be used including provision of work samples and teacher observation.

Individual Education Plans (IEPs)[3] may be used to describe personalised learning and support strategies including adjustments that are put in place for students with additional needs including disabilities. In the Australian context, IEPs are called by different names across different jurisdictions but they are all essentially a personalised plan for learning that records students’ progress against goals (Varvisotis et al. 2017).

IEPs can be made by the SSG where the goals and strategies for student learning are negotiated collaboratively. Teachers may record SMART[4] goals as agreed during the SSG meeting and report against these goals. IEPs can then be reviewed at regular intervals to evaluate the effectiveness of different strategies to ensure the teacher, family and student are satisfied with student progress. IEPs may describe student academic goals and can include goals related to health, interpersonal skills, self-care, mobility, behaviour and communication, depending on what the SSG prioritise for each student. The IEP can also incorporate information from any academic assessments conducted by teachers or other members of the SSG which can inform the goals developed.

Each state and territory in Australia has a specified process for implementing consultation and developing personalised plans. IEPs are compulsory for students with disability in some states (e.g., Victoria) but not in others (e.g., NSW) and regulations vary across systems. School leaders should make sure they are aware of the requirements within their particular system and jurisdiction. Teachers require support from school leadership to develop IEPs and conduct SSGs, including time, dedicating space and release of relevant staff for these meetings and subsequent planning.

3. Provide personalised adjustments

Adjustments are “actions taken to enable a student with disability to access and participate in education on the same basis as other students. Adjustments reflect the assessed individual needs of the student” (NCCD 2020a). Adjustments may be planned by the student’s support group and can be made at the whole-school level, in the classroom and at an individual student level. Adjustments will vary based on the assessed needs of the student, the resourcing and the environment of the school.

In providing an adjustment, schools assess the functional impact of the student's disability in relation to education. This includes the impact on communication, mobility, curriculum access, personal care and social participation. Other areas that might be considered for some students are safety, motor development, emotional wellbeing, sensory needs and transitions (NCCD 2020a).

Effective teaching that accommodates personalised adjustments is aided by careful planning. Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is one approach to planning for inclusive, personalised learning that aims to give all students an equal opportunity to succeed (Hall, Meyer & Rose 2012). The approach offers flexibility in the ways students access material, engage with it and show what they know.

Students with disabilities usually require alternative ways to access learning materials or activities. Applying UDL can help teachers plan in a way that allows students to perform a wide range of activities that ensures all students can understand the demands of the learning tasks and demonstrate their learning.

Universal Design for Learning

The Universal Design for Learning framework supports teachers to develop lesson plans and assessments that accommodate all learners. It is based on three main principles:

- Engagement: Look for multiple ways to motivate students. Provide choices and give assignments that are relevant to their lives to sustain students’ interest.

- Representation: Offer information in more than one format. Lots of educational resources are primarily visual but if teachers provide a mix of formats - text, audio, video and hands-on learning - it gives all students a chance to access the material in whichever way is best suited to their needs.

- Action and expression: Provide students more than one way to interact with the material and to show what they learn. For example, students choose between taking a pencil-and-paper test, giving an oral presentation or making a movie.

http://udlguidelines.cast.org

Watch: Using universal design principles to support every student

This webinar hosted by Learning Difficulties Australia includes in-depth worked examples by Dr. Kate deBruin of how to identify potential barriers and appropriate adjustments.

https://youtu.be/W26pzgozUxY?t=1114

Creating an inclusive classroom culture

This fact sheet outlines strategies for creating an inclusive classroom culture

4. Monitor and review the impact of adjustments

For students with a disability, the process of continually monitoring and reviewing the effectiveness of personalised learning support is important in order to “assess the progress of learning within the context of curriculum areas and find solutions to enhance the trajectory of learning of each student, ideally based on a strength-based approach” (Bowles et al 2016, p. 21).

A schoolwide framework used in many contexts to facilitate the monitoring and reviewing process for students with persistent learning difficulties and disabilities is Response to Intervention (RTI). The RTI process focuses on the relationship between teaching methods, effectiveness and student outcomes. Teachers assess how well students respond to initial instruction (primary level of intervention – Table 1), then make changes to instruction to achieve the students’ goals and best respond to their learning needs (Hughes & Dexter 2011). This may involve the provision of more personalised support if a student is struggling with a particular skill or lesson. RTI is characterised by a three-tier model of school supports centred in research-based academic and/or behavioural interventions, targeted to the differing needs of students. These tiers align to the first three levels used in the NCCD as shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Mapping of RTI and NCCD levels of adjustment

|

Instruction / Intervention

|

RTI Tier

|

Target student group

|

NCCD levels of adjustment

|

|

Universal high-quality instruction, screening, and group interventions available to every student in the class

|

Tier 1

|

Primary level of intervention - All students

|

Quality Differentiated Teaching Practice

|

|

Targeted interventions that are delivered to small groups, for a specific purpose, over a defined period of time, with time sensitive targets

|

Tier 2

|

Secondary level of intervention – around 15% of students considered to require additional supports

|

Supplementary Adjustments

|

|

Intensive interventions and/or comprehensive evaluation, often delivered 1:1 or 1:2, over an extended period, possibly for the entire length of schooling

|

Tier 3

|

Tertiary level of intervention – around 5% of students receiving intensive, personalised supports

|

Substantial Adjustments

|

|

Intensive, individualised instruction or support in a highly structured or specialised manner for all courses and curricula, activities and assessments, enabling access to learning through specialised equipment, highly modified classroom and/or school environments, extensive support from specialist staff.

|

Extensive Adjustments

|

Most states and territories use this model in some form, some applying interventions targeting student behaviour, and others taking a broader view of RTI as a framework to address student learning in academic, behavioural and social-emotional domains (Stoiber & Gettinger 2016).

By monitoring and tracking learning progress, teachers shift the focus of personalised learning and support toward the delivery and evaluation of instruction, and away from the provision of resources and support based solely on diagnosis or classification of disability.

The responsibility for educating a student with disability is one shared by the student’s teachers, school and support systems. As part of implementing agreed plans and adjustments teachers are involved in the granular, day-to-day cycle of planning, teaching and monitoring their student’s progress. Since students come to the classroom with a diverse range of learning needs, teachers need a rich set of strategies to draw upon to meet these needs. The following set of strategies can be used to support delivery and instruction for students with disability.

Physical adjustments

A student with limited mobility may require specialised furniture and may require specialised tools for writing or communicating their learning if they cannot hold a pencil or type easily. Similarly, a student with visual impairments may require a slope board, materials with enlarged text and textured or physical objects to hold and feel to help them learn about a specific topic or concept. Other strategies include:

- adjusting the physical or virtual classroom space

- using some form of adaptive or assistive technology, or sign language

- preparing modified material, with content that has alternative visual and auditory elements.

Learning difficulties

Teaching strategies that prove effective for students with intellectual restrictions or learning difficulties are in fact strategies that are effective for all students. For example, teachers may work with smaller groups or even one-on-one to enable specific targets to be set for each student, to deliver explicit instruction, and provide plenty of drill and practice for foundational concepts.

As a guide, some recommended practices include:

- direct teaching of skills, and practice to establish these skills

- frequent questions to stimulate thinking and check for understanding

- appropriate pacing and sequencing of lessons

- concepts that are developmentally appropriate

- use of real-life problems (Westwood 2017).

In a whole class setting, examples of adjustments that some students may need include the use of aids such as:

- concrete materials, for example counters when doing arithmetic

- computer or calculator to check results

- pictorial or textured charts to aid communication

- peer tutoring

- additional time to complete a test.

Social and practical skills

Some students may also require support to develop social skills and there are many strategies available to assist teachers to guide students in this area. For example, task analysis is a useful strategy for teaching students to do things like eat their lunch in the playground, complete the morning arrival routine, or complete and turn in assignments. Teachers can use task analysis to break procedural tasks into a sequence of logical smaller steps or actions for students to learn. Watching a demonstration of the task and documenting the steps also helps students recognise what is expected in specific situations (Pratt & Steward 2020).

Video modelling is another strategy that can be used to teach practical skills and increase positive behaviours. It is a teaching method where an individual watches a video of someone completing an activity and imitates the activity themselves. Teachers can use a task analysis for the skill being targeted and record someone performing the task based on the task analysis. The learner watches the video and then performs the task with least to most prompting. This strategy works best if the videos can be played on portable devices so they can be viewed immediately preceding the task.

Classroom management

Despite evidence that disciplinary and punitive approaches to managing behaviour for students with disability is outmoded (Zaglas 2020), these students experience higher rates of suspension and expulsion from school than students without disability (Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability 2019, p. 3). This suggests management of behaviour is a challenge for schools. Effective teaching practice for students who have difficulty with self-regulation include the:

- provision of structure and predictability

- frequent reinforcement of appropriate behaviour

- praise given to students for on-task behaviour and preparedness

- use of clear, simple instructions that describe what students need to do.

It is important to provide appropriate learning opportunities at the student’s developmental level to ensure that they can achieve and succeed and thus remain engaged with their learning. Some strategies teachers can use to help minimise students’ feelings of frustration include:

- break large tasks down into smaller steps

- use visual signals to support instructions about “what to do and how to do it”

- follow tasks with which the student struggles with a preferred activity

- give students opportunities to choose activities, ensuring some choices involve preferred tasks or materials and settings.

A whole school focus on behaviour can enhance the overall emotional climate of the school for the better. Schools that use prevention programs that establish schoolwide rules and expectations related to student and teachers’ behaviour can improve the social norms across classroom settings (Bradshaw et al. 2009; Sugai & Horner 2006). This not only reduces students’ disruptive behaviours and suspensions (Bradshaw, Waasdorp & Leaf 2012), but positively influences the way teachers view their students’ behaviour (O’Brennan et al. 2014; Freeman et al. 2016).

Positive Behavioural Interventions and Supports

An increasingly used prevention model, Positive Behavioural Interventions and Supports (PBIS) has been shown to significantly improve staff members’ perceptions of school climate, as well as reducing students’ disruptive behaviours and suspensions (Bradshaw et al. 2009, 2012). Also known as School-Wide Positive Behaviour Support (SWPBS)[5] it uses a three-tier intervention model to address school-wide needs for connectedness among students, teachers, and administrators, and also provides specific behaviour management skills to staff that can help reform antisocial behavioural norms within the classroom and across different contexts.

School-Wide Positive Behaviour Support

The School-Wide Positive Behaviour Support approach integrates planning and monitoring through a multi-tiered support structure based on Response to Intervention.

- Tier 1 primary prevention: supports for all students, staff and settings

- Tier 2 secondary prevention: additional specialised group systems for students with at-risk behaviour

- Tier 3 tertiary prevention: specialised, individualised systems for students with high-risk behaviour, provided in addition to primary and secondary prevention

Key features of the approach

- Establish a common philosophy and purpose

- Establish leadership and school-wide support for implementation

- Clearly define a set of expected behaviours that are positively stated and are identified and displayed in different school settings

- Establish procedures for teaching and practising expected behaviours

- Implement a continuum of procedures to encourage expected behaviours (awards and privileges)

- Develop a continuum of procedures to discourage inappropriate behaviour with specific and understood procedures in response to behavioural infractions

- Use procedures for record-keeping, decision making and ongoing monitoring by collecting and reporting on behavioural data

- Support staff to use effective classroom practices by establishing systems to support staff to adopt evidence-based instructional practices (DET VIC 2020)

Functional Behaviour Assessment

Functional behaviour assessment (FBA) is a systematic set of strategies that is used to determine the underlying function or purpose of a behaviour, so that an effective intervention plan can be developed. FBA consists of describing the interfering or problem behaviour, identifying events that influence the behaviour, developing a theory about the function of the behaviour, and testing the theory. It acknowledges that student behaviour occurs in response to a mixture of biological, psychological and social conditions that may not be immediately obvious. To conduct a Functional Behaviour Assessment teachers note:

- The form of the behaviour in detail: What is the student actually doing?

- The context of behaviour including the environmental setting, the personal circumstances that influence a student: Where does the behaviour occur and what happens immediately before and after?

- The function of the behaviour: What does the student avoid or gain from undertaking the behaviour? (NSW DoE 2019)

The ‘function’ of the behaviour may have tangible, sensory and/or psychological elements. Identifying these pieces of key functions allows teachers to design strategies and interventions that improve the student behaviour by meeting their needs in more prosocial ways.

Guided Functional Behaviour Assessment Tool

This tool from the Queensland Government’s Autism Hub and Reading Centre is designed to help teachers understand, effectively respond to and prevent frequent minor behaviours. It leads to a wealth of further practical resources and strategies.

https://ahrc.eq.edu.au/services/fba-tool

Evidence from a variety of sources continue to demonstrate that students with disability (and their families) face exclusion, and in some cases, victimisation in Australian schools. For example, in an Australian survey conducted in 2016, over 70% of families of a student with disability reported experiencing gatekeeping or restrictive practices in schools (Poed, Cologon & Jackson 2020). It is concerning that physical, verbal and social victimisation of students with autism is described in responses to the Royal Commission Education Issues paper (2020, p. 2).

Similarly, in a survey[6] conducted by Mission Australia more than twice the number of young people (aged 15-19) living with disability had experienced bullying in the past twelve months (43%) compared with respondents without disability (19%). This included physical bullying (e.g. hitting, punching) and cyberbullying (e.g. hurtful messages, pictures or comments) (Hall et al. 2020). For these young people, levels of concern about mental health, suicide, and bullying and emotional abuse were higher when compared with respondents who did not identify as living with a disability. This survey also highlights that young people with disability are experts in their own lives and needs. When asked about post-school plans, young people living with disability want to go to university (48%), get a job (40%), travel/have a gap year (24%), go to TAFE or college (20%), or get an apprenticeship (15%) (Hall et al. 2020).

Programs and services for those with disability should be informed and co-designed by people with disability. Schools have a key role to play in ensuring educational services and programs support all the aspects of a young person’s life (Hall et al. 2020). This includes enacting the Disability Standards for Education (2005), namely to “promote recognition and acceptance within the community of the principle that persons with disabilities have the same fundamental rights as the rest of the community” (p. 8). This goes beyond ensuring a learning environment free from discrimination, harassment or victimisation on the basis of disability. It involves working to build a school community in which all members feel they belong, are accepted by peers, connected to friends and supported by key adults. A positive lived experience of inclusion fosters a school-wide culture of respect and belonging and provides a natural opportunity for everyone in the community to learn about and celebrate individual differences. Teachers play an important role in modelling expectations for students with disability, which can influence the expectations and attitudes of other students (Robinson & Truscott 2014).

The sum of all the strategies and phases outlined above, when implemented appropriately, is a truly inclusive school environment, one where all students are afforded high quality educational experiences. As schools and society work to move beyond historical patterns of hiding or ignoring disability, it is important to hear all voices: students with disability, their families, their classmates and those in teaching, leadership and support roles. Each person has learning needs and the challenge is to determine how these are best met, at the same time improving their experience of learning, and providing the support each needs to build their confidence and do their best. All school staff have a role to play in creating a truly inclusive school environment, especially teachers and school leaders.

Working together – supporting students during transitional periods

Transitions to school, between activities and classes, and between primary and secondary, to post-school options can be a difficult experience for students with disability (Pitt, Dixon & Vialle 2019; Richter, Popa-Roch & Clément 2019). To enable effective transitions, it is important for teachers and support teams to be proactive in planning and preparing for changes in a student’s schooling. The goal is to give learners confidence, and to reduce anxiety during transitions (Sugai et al. 2016). During transition phases, teachers can help prepare students for the next stage by working together with parents and the SSG to develop contingencies to support the student. Teachers can also help reduce student anxiety by explaining the transition in ways that students can understand.

Teachers

In studies on attitudes towards inclusive education, both teachers and pre-service teachers consistently affirm the importance of inclusion of students with disability (Carrington et al. 2016; Goddard & Evans 2018; Loreman, Sharma & Forlin 2013). They also highlight challenges faced in resourcing inclusion (Walsh 2012), and concerns relating to their professional competence, achievement levels of students with special educational needs, and managing challenging behaviours and on-task engagement in the classroom (Cook et al. 2000; Round, Subban & Sharma 2016).

Submissions to the Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability (2019) suggest that educators require support and training to better understand inclusive education and how to build classroom environments that support the needs of all students. The Royal Commission heard that when funding is provided for professional learning opportunities in disability, courses are quickly filled with teachers keen for the extra study (Alderslade 2019).

When implemented, professional learning “is pivotal in developing the affirmative attitudes and skills required for successful inclusion, with formal educational training being identified as one of the main factors that promote an inclusive attitude” (Vaz et al. 2015, p. 2). Despite the power of professional learning to promote inclusive teaching practices, teachers report that “there is generally a lack of opportunities to view good practices” (Forlin & Chambers 2017). It is promising that teachers report opportunities to shadow an experienced teacher working with students who share similar needs to be a powerful form of professional learning. Shadowing an experienced teacher is one way of enabling teachers to view examples of good practice – other ways include video case studies, observation and collaboration. This suggests there is potential for schools to promote collaboration among their teaching staff to support each other in this space.

School leaders

School leaders have an important role in navigating the support context for students with disability. Funding, reporting and accountability requirements for programs for students with disability vary according to the student, the jurisdiction, and available resources. The Principal’s role also involves ensuring the school meets the Disability Standards for Education 2005 in the areas of:

- enrolment

- participation

- curriculum development, accreditation and delivery

- student support services

- elimination of harassment and victimisation

School leaders have the challenge of interpreting key concepts relating to students with disability and providing guidance to their staff. For example, key aspects of the disability standards, including ‘reasonable adjustments’ require careful attention. Similarly, schools are required by the standards to meet the needs of students with disability ‘on the same basis’ as other students – here, ‘same’ does not mean identical or equal, but rather equitable (Duncan et al. 2020). It is up to the school leader to guide teachers through implementing these adjustments.

Teacher assistants

Teacher assistants often provide direct student support in a one-to-one or small group context. Training specific to their duties is important. It is recommended that teaching assistants provide general classroom support and deliver specific programs under teacher direction, rather than ad hoc individual assistance, and that they not be required to plan instruction (Carter, Stephenson & Webster 2019; Gibson, Paatsch & Toe 2016).

The Disability Standards for Education 2005 charge teachers and school communities to ensure accessibility of education for students with disability. Accessibility goes well beyond access to school enrolment, facilities, buildings, and education materials. It includes access to the same curriculum, teaching and educational opportunities as other students their age, and participation in school activities such as excursions, assemblies, or sports. Schools are also required to protect students with disability from violence, abuse, neglect and exploitation (Royal Commission 2020). In sum, schools should be inclusive spaces where all students are afforded opportunities to thrive.

Inclusive education involves teachers, leaders, students, parents and support teams working together to directly target the needs of each student. The NCCD’s four elements of personalised learning, outlined here, form the basis of an effective process to enhance the learning experience of students with disability:

- consultation and collaboration with the student and/or parents or carers

- assessing and identifying the needs of the student

- providing reasonable adjustments to address the identified needs of the student

- monitoring and reviewing the impact of adjustments (NCCD 2020a)

Through careful attention to the progress of each student’s learning, and the provision of appropriate adjustments, teachers, school leaders and school communities can support all students to succeed. Building a culture of inclusion is a vital step towards the elimination of discrimination against students with disability in Australian schools.

Get the latest news and updates from AITSL

Join 180,000+ AITSL Mail subscribers and recieve tools and resources for Teachers and School Leaders

Sign up today

Footnotes

- First year of formal schooling

- Assessments such as Early Start (QLD), Mathematics Online Interview, English Online Interview and the Diagnostic Assessment Tools in English (Victoria), Best Start Kindergarten Assessment (NSW)

-

Individual Learning Plans (ILPs) in Catholic jurisdictions; Individual Curriculum Plans (ICPs) in Queensland; Negotiated Education Plans (NEPs) in South Australia

-

Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic and Timely (SMART) goals

-

This approach has been endorsed by education departments in Queensland, New South Wales and Victoria (DoE NSW 2019; DoE QLD 2018; DET VIC 2018)

-

There were 25,000 young people aged between 15 and 19 who participated in Youth Survey 2019, and of those 1,623 reported a disability.

Alderslade, L 2019, ‘Teachers are not trained in inclusive

education’, Disability Support Guide, viewed 4 October 2020,

<https://www.disabilitysupportguide.com.au/talking-disability/royal-commission-teachers-are-not-trained-in-inclusive-education>.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2019, Disability,

Ageing and Carers, Australia: Summary of Findings, 2018, viewed 4 October 2020,

<https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/[email protected]/Latestproducts/4430.0Main%20Features12018>.

Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority

(ACARA) 2016, Student diversity, viewed 4 October 2020,

<https://www.acara.edu.au/curriculum/student-diversity>.

Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership

(AITSL) 2011, Australian Professional Standards for Teachers, viewed 7 October

2020, <https://www.aitsl.edu.au/teach/standards>.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2019,

‘School (primary and secondary)’, People with disability in Australia, viewed 4

October 2020, <https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/34f09557-0acf-4adf-837d-eada7b74d466/Education-20905.pdf.aspx>

Bowles, T et al. 2016, ‘Conducting psychological assessments

in schools: Adapting for converging skills and expanding knowledge’, Issues in Educational Research, vol. 26,

no. 1, pp. 10-28, viewed 4 October 2020

<http://www.iier.org.au/iier26/bowles.pdf>.

Bradshaw, CP et al. 2009, ‘Altering school climate through

School-Wide Positive Behavioral interventions and supports: Findings from a

group-randomized effectiveness trial’, Prevention

Science, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 100–115,

<https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-008-0114-9>.

Bradshaw, CP, Waasdorp, TE & Leaf, PJ 2012, ‘Effects of

School-Wide Positive Behavioral interventions and supports on child behavior

problems’, Pediatrics, vol. 130,

no. 5, e1136-e1145, <https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-0243>.

Carrington, S et al. 2016, ‘Teachers’ experiences of

inclusion of children with developmental disabilities across the early years of

school.’, Journal of Psychologists and

Counsellors in Schools, vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 139–154,

<https://doi.org/10.1017/jgc.2016.19>.

Carter, M, Stephenson, J & Webster, A 2019, ‘A survey of

professional tasks and training needs of teaching assistants in New South Wales

mainstream public schools’, Journal of

Intellectual & Developmental Disability, vol. 44, no. 4, pp.

447–456, <https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2018.1462638>.

Cook, BG, Tankersley, M, Cook, L & Landrum, TJ 2000,

Teachers’ attitudes toward their included students with disabilities. Exceptional Children, vol. 67, no. 1, pp. 115-135,

<https://doi.org/10.1177/001440290006700108>.

Declaration on the Rights of Disabled Persons 1975, viewed 4

October 2020,

<https://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/RightsOfDisabledPersons.aspx>.

Department of Education and Training (DET) 2015, Planning for personalised learning and support: A

national resource, viewed 7 October 2020,

<https://docs.education.gov.au/documents/planning-personalised-learning-and-support-national-resource-0>

Department of Education and Training Victoria (DET VIC) 2020,

School-wide positive behaviour support (SWPBS) framework, viewed 5 October

2020, <https://www2.education.vic.gov.au/pal/behaviour-students/guidance/5-school-wide-positive-behaviour-support-swpbs-framework>.

Department of Education NSW (DoE NSW) 2019, Functional

Behaviour Assessment: What is the function of the behaviour?, viewed 5 October

2020

<https://education.nsw.gov.au/content/dam/main-education/student-wellbeing/attendance-behaviour-and-engagement/media/documents/Functional-Behaviour-Assessment-fact-sheet.pdf>.

Department of Education Queensland (DoE QLD) 2018, Students

with disability program 2018, viewed 5 October 2020,

<https://education.qld.gov.au/about-us/budgets-funding-grants/grants/non-state-school/students-with-disability-program>.

Department of Education, Skills and Employment (DESE) 2020,

Discussion Paper - 2020 Review of the Disability Standards for Education 2005,

viewed 4 October 2020,

<https://disabilitystandardsreview.education.gov.au/discussion_paper>.

Disability Discrimination Act 1992, viewed 4 October 2020,

<https://www.legislation.gov.au/Series/C2004A04426>.

Disability Standards for Education 2005, Department of

Education, Skills and Employment, viewed 4 October 2020,

<https://docs.education.gov.au/system/files/doc/other/disability_standards_for_education_2005_plus_guidance_notes_0.pdf>.

Duncan, J et al. 2020, ‘Missing the mark or scoring a goal?

Achieving non-discrimination for students with disability in primary and

secondary education in Australia: A scoping review’, Australian Journal of Education, vol. 64, no. 1, pp. 54–72,

viewed 5 October 2020, <https://doi.org/10.1177/0004944119896816>.

Forlin, C & Chambers, D 2017, ‘Catering for diversity:

including learners with different abilities and needs in regular classrooms’,

in R Maclean (ed.), Life in schools and

classrooms: Past, present and future, Springer, Singapore,

pp.555–571, <http://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-3654-5_33>.

Freeman, J. et al. 2016, ‘Relationship between School-Wide

Positive Behavior interventions and supports and academic, attendance, and

behavior outcomes in high schools’, Journal

of Positive Behavior Interventions, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 41–51,

<https://doi:org/10.1177/1098300715580992>.

Gibson, D, Paatsch, L, & Toe, D 2016, ‘An Analysis of the

Role of Teachers’ Aides in a State Secondary School: Perceptions of Teaching

Staff and Teachers’ Aides’, Australasian Journal of Special Education, vol. 40,

no. 1, pp. 1–20. <https://doi.org/10.1017/jse.2015.11>.

Goddard, C & Evans, D 2018, ‘Primary pre-service teachers’

attitudes towards inclusion across the training years’, Australian Journal of Teacher Education,

vol. 43, no. 6, pp. 122-142. <https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2018v43n6.8>.

Hall, S et al. 2020, Young willing and able: youth survey

disability report 2019, Mission Australia, Sydney, viewed 2 October 2020,

<https://www.missionaustralia.com.au/publications/youth-survey/1610-young-willing-and-able-youth-survey-disability-report-2019>.

Hall, TE, Meyer, A, & Rose, DH (eds.) 2012, Universal design for learning in the classroom: Practical

applications, Guilford Press, New York.

Hughes, CA & Dexter, DD 2011, ‘Response to Intervention:

A research-based summary’, Theory into

Practice, vol. 50, no. 1, pp. 4–11,

<https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2011.534909>.

Loreman, T, Sharma, U, & Forlin, C 2013, ‘Do pre-service

teachers feel ready to teach in inclusive classrooms? A four country study of

teaching self-efficacy.’, Australian Journal

of Teacher Education, vol. 38, no. 1, pp. 27-44. <https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2013v38n1.10>.

Mitchell, D 2015, Education that fits: Review of

international trends in the education of students with special educational

needs, Department of Education and Training, Melbourne, Vic., viewed 5 October

2020, <https://www.education.vic.gov.au/Documents/about/department/psdlitreview_Educationthatfits.pdf>.

Nationally Consistent Collection of Data on School Students

with Disability (NCCD) 2019, 2019 guidelines, viewed 4 October 2020,

<https://www.nccd.edu.au/sites/default/files/nccd_guidelines.pdf>.

Nationally Consistent Collection of Data on School Students

with Disability (NCCD) 2020a, viewed 4 October 2020,

<https://www.nccd.edu.au>.

Nationally Consistent Collection of Data on School Students

with Disability (NCCD) 2020b, Personalised learning and support, viewed 4

October 2020,

<https://www.nccd.edu.au/personalised-learning-and-support>.

Nowak, S & Jacquemont, S 2020, ‘The effects of sex on

prevalence and mechanisms underlying neurodevelopmental disorders’, in A

Gallagher, C Bulteau, D Cohen, & JL Michaud (eds), Handbook of Clinical Neurology, Elsevier

B.V., pp. 327–339.

O’Brennan, LM, Bradshaw, CP, & Furlong, MJ 2014,

‘Influence of classroom and school climate on teacher perceptions of student

problem Behavior’, School Mental Health,

vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 125–136.

Pitt, F, Dixon, R, & Vialle, W 2019, ‘The transition

experiences of students with disabilities moving from primary to secondary

schools in NSW, Australia’, International

Journal of Inclusive Education, pp. 1–16,

<10.1080/13603116.2019.1572797>.

Poed, S, Cologon, K, & Jackson, R 2020, ‘Gatekeeping and

restrictive practices by Australian mainstream schools: results of a national

survey’, International Journal of Inclusive

Education, pp. 1–14,

<https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2020.1726512>.

Pratt, C & Steward, L 2020, Applied behavior analysis:

The role of task analysis and chaining, Indiana Resource Center for Autism,

viewed 5 October 2020, <https://www.iidc.indiana.edu/irca/articles/applied-behavior-analysis.html>.

Richter, M, Popa-Roch, M, & Clément, C 2019, ‘Successful

transition from primary to secondary school for students with autism spectrum

disorder: A systematic literature review’, Journal

of Research in Childhood Education, vol. 33, no. 3, pp. 382–398,

<https://doi.org/10.1080/02568543.2019.1630870>.

Robinson, S & Truscott, J 2014, Belonging and connection

of school students with disability, Children With Disability Australia, Clifton

Hill, Victoria, viewed 5 October 2020,

<https://www.cyda.org.au/images/pdf/belonging_and_connection_of_school_students_with_disability.pdf>.

Round, PN, Subban, PK & Sharma, U 2016, ‘I don't have

time to be this busy.’ Exploring the concerns of secondary school teachers

towards inclusive education, International Journal of Inclusive Education, vol.

20, no. 2, pp. 185-198, <https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2015.1079271>.

Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and

Exploitation of People with Disability 2019, Education

and learning: Issues paper, viewed 4 October 2020,

<https://disability.royalcommission.gov.au/publications/education>.

Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability 17 June 2020, The Australian Government’s Background Paper on the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Part 2 – The right to education in article 24, <https://disability.royalcommission.gov.au/system/files/2020-09/Australian%20Government%20Position%20Paper%20on%20the%20UNCRPD%20-%20Part%202%20-%20The%20right%20to%20education%20in%20article%2024.pdf>

Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability 2020 July, Overview of responses to the first education and learning Issues paper,

viewed 4 October 2020, <https://disability.royalcommission.gov.au/system/files/2020-08/Overview%20of%20responses%20to%20the%20first%20Education%20and%20learning%20Issues%20paper.pdf>

Stoiber, KC & Gettinger, M 2016,‘Multi-tiered systems of

support and evidence-based practices’, in MK Burns, SR Jimerson, & AM

VanDerHeyden (eds.), Handbook of Response to

Intervention: The Science and Practice of Multi-Tiered Systems of Support,

Springer, New York, NY, <https://doi.org/10.1007%2F978-1-4899-7568-3_9>.

Sugai, G & Horner, RR 2006, ‘A promising approach for

expanding and sustaining School-Wide Positive Behavior Support, School Psychology Review, vol. 35, no. 2,

pp. 245-259.

Sugai, G et al. 2016, ‘Capacity development and multi-tiered

systems of support: Guiding principles’, Australasian Journal of Special

Education, vol. 40, no. 2, pp. 80–98,

<https://doi.org/10.1017/jse.2016.11>.

Vaz, S et al. 2015, ‘Factors associated with primary school

teachers’ attitudes towards the inclusion of students with disabilities’, PLoS ONE, vol. 10, no. 8, <https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0137002>.

Varvisotis, S, Matyo-Cepero, J, & Ziebarth-Bovill, J

2017, ‘An intentionally inviting individualized educational program meeting: It

can happen!’ Journal of Invitational Theory

and Practice, vol. 23, pp. 85–90, viewed 4 October 2020,

<http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1184556.pdf>.

Walsh, T 2012, ‘Adjustments, accommodation and inclusion:

Children with disabilities in Australian primary schools’, International Journal of Law and Education,

vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 33–48.

Westwood, P 2017, Learning

disorders: A Response-to-Intervention perspective, Routledge,

London, viewed 5 October 2020,

<https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/9781315174228>.

Zaglas, W 2020, ‘Expert tells royal commission “manage and

discipline model” is failing students with a disability | Education Review’, Education Review, viewed 20 October 2020,

<https://www.educationreview.com.au/2020/10/expert-tells-royal-commission-manage-and-discipline-model-is-failing-students-with-disability/>.