The key messages in this Spotlight reveal that:

- Australia’s teachers and school leaders are highly committed and motivated, investing considerable time into their own professional learning to improve the quality of teaching and learning for their students. Across the OECD countries,

Australia has one of the highest participation rates in professional learning.

- Concerningly, our teachers and school leaders are collaborating and meeting less frequently for professional learning compared to before the COVID-19 pandemic. High-Quality Professional Learning cultures are underpinned by collaborative practices,

which harness collective power to deepen professional learning and drive practice excellence.

- The professional learning landscape has changed. Technology-rich learning and administrative environments are being developed and the primary mode of professional learning has shifted to online activities. There has been a marked decline in

face-to-face learning courses being undertaken outside of the workplace.

- Selection of professional learning activities should be based on individual teacher needs, whole-school priorities and align with expectations set by systems, sectors and teacher regulatory authorities.

- Leaders can support teacher agency through a variety of strategies while balancing overarching priorities.

- Professional learning activities are being guided by the Australian Professional Standards for Teachers (Teacher Standards). However, there is room for improvement through aligning professional learning activities and embedded goals more explicitly

to the Teacher Standards.

Quality teaching and school leadership relies on ongoing applied learning and reflective practice. At its most effective, professional learning develops individual and collective capacity across the teaching profession to address current and future

challenges (AITSL, 2012; Darling-Hammond et al., 2017). Professional learning undertaken by teachers and school leaders focuses on both individual contexts and collaborative school goals.

Professional learning encompasses formal and informal learning experiences undertaken by teachers and school leaders that improve their individual professional practice and the school’s collective effectiveness, with the aim of improving student

outcomes (AITSL, 2018; Cole, 2012). A variety of modes and approaches to professional learning are commonly undertaken by teachers and school leaders across Australia (Figure 1). The various modes are often combined in learning activities, either

concurrently (e.g., online learning & research reading) or consecutively (e.g., professional conversation leading to coaching or mentoring). High-Quality Professional Learning (HQPL) is relevant, collaborative and future-focused, and based

on a strong foundation of reflective practice that is guided by the Australian Professional Standards for Teachers (Teacher Standards) and the Australian Professional Standard for Principals (Principal Standard). HQPL empowers teachers and school

leaders to develop professional knowledge and practice for improving students’ learning, engagement, and wellbeing.

Figure 1. Main types of professional learning activities

While professional learning is centred around meeting situational needs, many contemporary factors shape educational goals and therefore learning requirements. Prime examples include technological advancement, digitalisation and growing student diversity

(cultural, linguistic & disabilities) (ACARA, 2018a, 2018b; OECD, 2019). The COVID-19 pandemic caused unprecedented challenges that forced considerable change across much of Australian schooling. The pandemic brought to the fore adaptive school

leadership, digitalisation, and the imperative for schools to maintain HQPL cultures (AITSL, 2017b, 2020b). Our teachers certainly rose to the challenges of the pandemic.

The increase in positive public perceptions of teachers’ work reflects an awareness of how teachers responded to the challenges faced during the crisis.

Heffernan et al., 2021, p3.

This Spotlight explores the professional learning landscape across Australia. AITSL conducted a four-week nationwide HQPL survey (commenced 14 November 2022), capturing firsthand professional learning experiences from 796 teachers and school leaders[1] from

all 3 sectors (Government, Independent & Catholic). The survey aimed to assess the professional learning landscape in schools across the country and understand any changes occurring over the last 5 years. Comparisons were made to previous

surveys, the AITSL HQPL survey undertaken in 2017 (AITSL, 2017c) and the AITSL Stakeholder Survey conducted in 2019, and through literature-based analyses over this timeline.

In 2022, AITSL finalised a three-year HQPL project that was initiated at the request of the then Minister for Education which, in part, focused on the development of online platforms to support teachers and school leaders with HQPL. This Spotlight

highlights the digital HQPL tools and resources created by AITSL. These resources were developed to assist teachers and school leaders with identifying professional learning needs, and with developing, implementing, and evaluating professional

learning plans. AITSL recognises that relevant, well-planned professional learning is crucial for improving the teacher-learning process and is committed to promoting HQPL cultures within our schools.

Teachers and school leaders in Australia are highly dedicated to professional learning, consistently boasting one of the highest participation rates among the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries (OECD, 2014, 2019).

Nearly all teachers in AITSL's HQPL 2022 (95%, n=451)[2] and 2017 (96%, n=700) surveys reported undertaking professional learning activities over previous 12-month periods. Similarly, almost all

school leaders (98%, n=127) and middle leaders (98%, n=188) undertook professional learning activities over the 12-months prior to the 2022 survey. This is unsurprising, given that Australian teachers are required to undertake professional learning

to demonstrate ongoing growth in professional practice and continued suitability to be registered in the teaching profession (AITSL, 2017a). Teachers nationwide complete at least 100 hours of professional learning over each 5-year term to maintain

full registration (AITSL, 2017a).

Motivations behind professional learning are value-based

Australia’s teachers and middle leaders participate in professional learning for all the right reasons; to improve their individual professional practice and to increase their school’s collective effectiveness for the betterment of students.

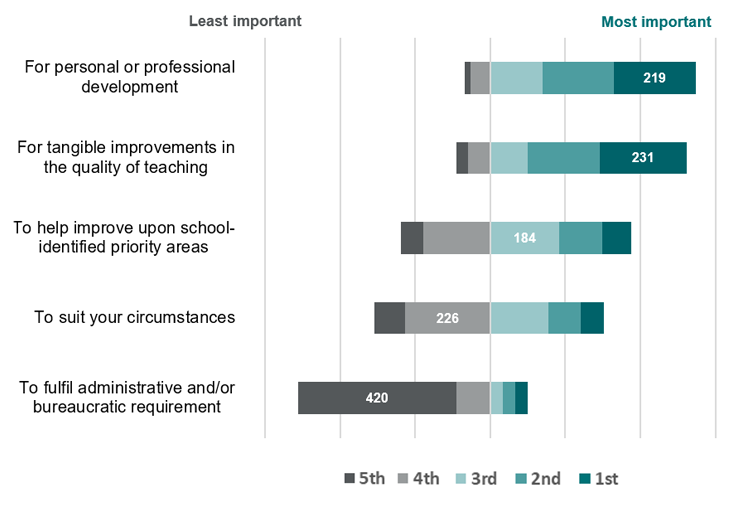

In AITSL's HQPL 2022 survey, teachers (n=444) and middle leaders (n=177) ranked the importance of five motivational elements for professional learning. ‘For personal or professional development’ was ranked as the most important motivation,

closely followed by ‘For tangible improvements in the quality of teaching’ (Figure 2). ‘To help improve upon school identified priority areas’ was most commonly ranked third, followed by ‘To suit your circumstances’.

Negligible importance was placed on ‘To fulfil administrative and bureaucratic requirements’ (Figure 2). Along with personal development and tangible improvements to teaching, emphasis on collaborative school goals suggests perceived

value in working together with colleagues to achieve common objectives. Collaboration can powerfully amplify the benefits of professional learning. This underscores the imperative for schools to create a HQPL culture, where teachers and leaders

are supported to work together on their learning endeavours.

Figure 2. Elements of professional learning most important to teachers & middle leaders

Continuous commitment to professional learning

Australia’s educators are dedicated to their professional practice, spending considerable time and effort on learning to improve the quality of teaching every year. AITSL's HQPL 2022 survey highlighted the commitment our education profession

has to professional growth across the workforce. Most teachers (60%, n=283), middle leaders (69%, n=133) and school leaders (74%, n=96) reported engaging in five or more separate professional learning activities over the past year. The average

time spent by all educators surveyed (n=735) on their most recent professional learning activity was 9.9 hours. Teachers reported 9.87 hours (n=434, SD[3] =12.07), middle leaders 9.14 hours (n=180,

SD=11.5) and school leaders 10.86 hours (n=121, SD=12.7). This has been consistent since 2017. When surveyed in 2017, a majority of teachers (52%, n=376) likewise reported undertaking five or more separate professional learning activities over

12-months, spending on average 9.8 hours (n=632, SD=10.6) on their most recent activity.

Other sources of data also indicate that teachers are heavily invested in professional learning. The Australian College of Educators (ACE) recently found that 81% of teachers (n=520) believe professional learning to be beneficial or very beneficial

(NEiTA–ACE, 2021). Many teachers reported contributing financially to their own professional learning (42%) and using online social networks to improve their teaching practice (75%). Teachers identified professional learning as being crucial

for improving skills in “motivating their students, using information technology, building strong relationships with their students, and applying real world scenarios in teaching” (NEiTA–ACE, 2021, p7). Taken together, these

findings suggest Australia’s educators are motivated, committed and pursue professional learning with the aim of supporting their students to thrive.

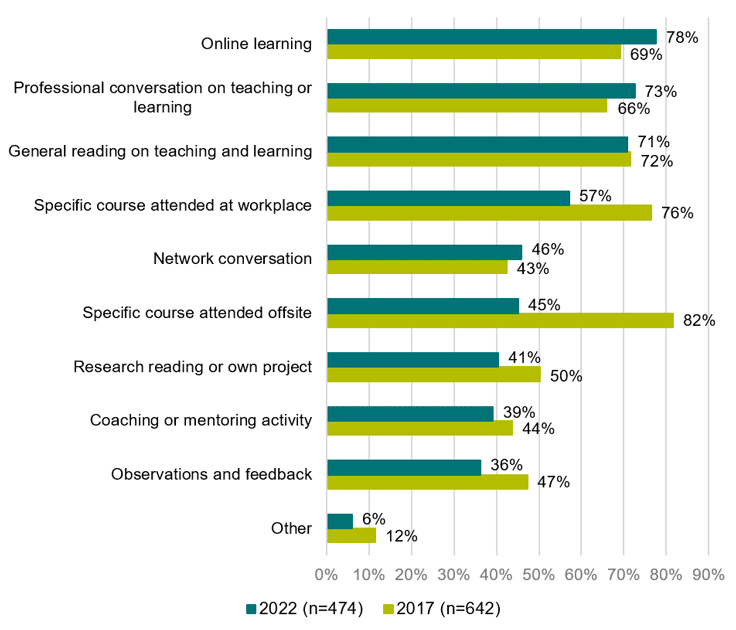

In AITSL’s HQPL 2022 and 2017 surveys, teachers were asked about the types of professional learning activities they had undertaken in the previous 12-months and reported engaging in a wide variety, providing great scope for meeting diverse and

contextualised learning needs. However, there has been a discernable shift in the popularity of mode of delivery over recent years. In 2017, teachers primarily reported attending specific courses delivered outside (82%) or within the workplace

(76%), followed by general reading (72%) (Figure 3). Whereas in the 2022 survey, teachers reported participating in more in-house learning, such as online learning (78%), professional conversations (73%) and general reading (71%), rather than

specific courses. Like teachers, middle leaders (n=192) reported online learning (86%), professional conversations (80%) and general reading (78%) as their topmost activities.

Figure 3. Types of professional learning activities undertaken by teachers, ordered by 2022 prevalence

The shift away from traditional in-person professional learning courses is likely due, at least in part, to the ongoing digitalisation of the education industry (Masters, 2018; OECD, 2020). The most recent OECD Teaching and Learning International

Survey (TALIS), conducted in 2018, found that Australian teachers mainly attended courses and workshops (86%) and then educational conferences (56%) for their professional learning (OECD, 2019). Data from the AITSL HQPL surveys indicate there

has since been a shift towards digitalisation (Figure 3).

Digitalisation in education requires, in addition to ICT infrastructure and integration into curricula, ongoing workforce training for developing technology-rich learning and administrative environments. Online teacher professional learning has concurrently

experienced explosive growth in the last decade (Lay et al., 2020; OECD, 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic undoubtedly accelerated this shift, as in-person workshops and courses were not feasible in many jurisdictions. Online professional learning

activities are more accessible, flexible, cost-effective and scalable (i.e., can reach many people) than traditional courses and workshops, which may make them more appealing to educators long-term. These sentiments were echoed throughout teacher

and school leader comments captured in AITSL’s HQPL 2022 survey.

"COVID changed the way much professional learning was delivered and opened the way for more online learning."

Deputy principal, primary school in Western Australia.

"COVID changed the way much professional learning was delivered and opened the way for more online learning."

Deputy principal, primary school in Western Australia.

"We do a lot of our training online now compared to very little 5 years ago."

Teacher, special education in South Australia.

"We do a lot of our training online now compared to very little 5 years ago."

Teacher, special education in South Australia.

"I now engage in online learning much more often."

Teacher, secondary school in Australian Capital Territory.

"I now engage in online learning much more often."

Teacher, secondary school in Australian Capital Territory.

"More online and on demand webinars now, whereas previously there were more face-to-face sessions. "

Teacher, primary school in Australian Capital Territory.

"More online and on demand webinars now, whereas previously there were more face-to-face sessions. "

Teacher, primary school in Australian Capital Territory.

"The increase in online delivery modes & free university short courses has made professional learning more accessible

& allowed for more options and opportunities across a range of topics."

Teacher, primary school in Queensland.

"The increase in online delivery modes & free university short courses has made professional learning more accessible

& allowed for more options and opportunities across a range of topics."

Teacher, primary school in Queensland.

"The increase in online learning opportunities has been very welcomed as I live in a regional area. Also, being able to

work through professional learning at my own pace is very useful."

Middle leader, combined school in South Australia.

"The increase in online learning opportunities has been very welcomed as I live in a regional area. Also, being able to

work through professional learning at my own pace is very useful."

Middle leader, combined school in South Australia.

Collaborative professional learning practices are in decline

Collaboration can improve the quality of professional learning activities, allowing the sharing of knowledge and expertise for building a culture of continuous learning and improvement (AITSL, 2017b, 2018; Darling-Hammond et al., 2017). When school

staff collaborate effectively, they “create a base of pedagogical knowledge that is distributed among teachers within a school as opposed to being held by individual teachers” (Brook et al., 2007). Other benefits of collaborative professional

learning include improved teacher effectiveness, increased job satisfaction, shared accountability and greater creativity and innovation. Nevertheless, in recent years, professional learning has seemingly shifted away from being collaborative,

to processes and structures that are more individual.

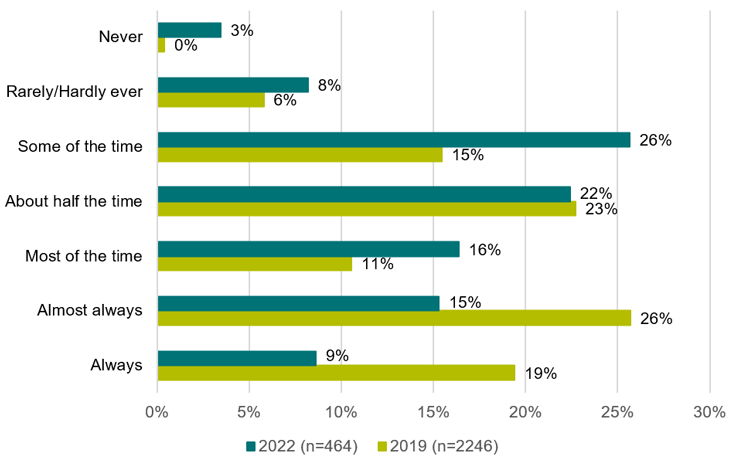

In AITSL’s HQPL 2022 survey, fewer teachers reported collaborating with colleagues than in the 2019 AITSL Stakeholder Survey, when the same question was asked prior to the pandemic (Figure 4). While nearly a quarter of teachers reported collaborating

'about half the time' in both survey years, the proportion who reported collaborating ‘almost always’ or ‘always’ dropped considerably from 2019 to 2022 (45% vs 24%); with over one quarter of teachers saying they collaborated

‘some of the time’ (2022: 26%)

Figure 4. How often teachers work collaboratively with colleagues during professional learning

As schools have increasingly structured teaching as a collaborative community endeavour, it makes sense that teacher collaboration is an important feature of well-designed professional development

Darling-Hammond et al., 2017, p9

The decline in collaborative professional learning practices could reflect a number of circumstantial changes, including increased workloads (time constraints) and teacher shortages, but it is interesting that a decrease in collaboration coincided

with the recent shifts in learning modalities (e.g., adapting to online modes). Some of these changes may have been influenced by the pandemic. However, given that collaboration can powerfully influence the quality of professional learning, it

may be valuable to find new ways to incorporate more collaborative practice across professional learning programs, including those conducted online.

Focus areas of professional learning

Educators constitute a heterogeneous group of professionals, with different roles imposing varied and often competing professional learning demands. Focus areas for professional learning are largely determined through self-reflection, feedback from

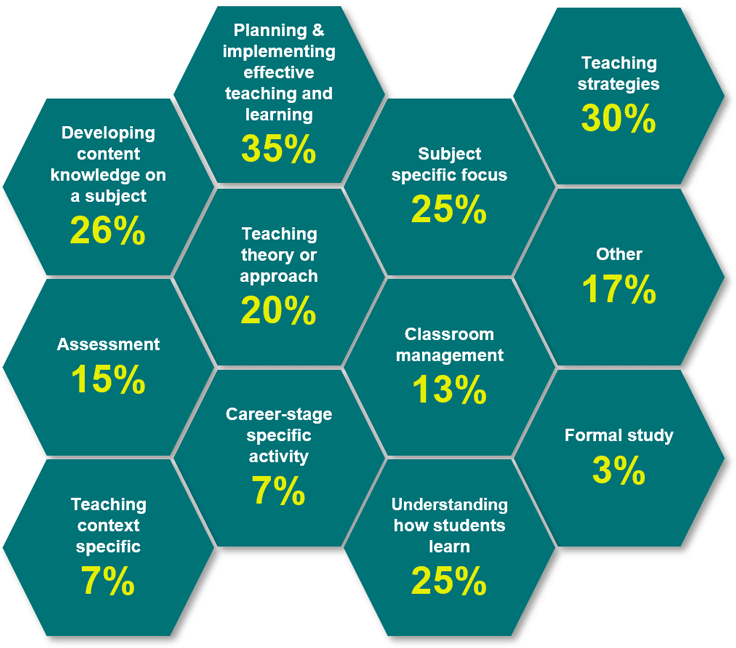

colleagues and students, analysis of student data, educational research, and through alignment with school-identified goals. Situational context plays a significant role in determining the focus of professional learning. In AITSL’s HQPL

2022 survey, teachers were asked to designate the focus areas of their most recent professional learning activity, and were able to select as many focus areas as were relevant. The three most reported focus areas were planning and implementing

effective teaching and learning (35%, n=150), teaching strategies (30%, n=132), and developing content knowledge on a subject (26%, n=111) (Figure 5). Formal study was an uncommon professional learning focus (3%) as was undertaking teaching context

specific related professional learning (7%).

Figure 5. Focus of professional learning activities undertaken by teachers

In the professional learning context, teacher agency refers to teachers having input into the professional learning activities they undertake, with the aim to realise impactful change on their own practice. With agency, teachers shape their professional

growth and learning environment and collaborate with school leaders to make professional learning decisions within the workplace context. The degree to which teachers act with agency depends on individual motivations and on workplace practices/policies,

including decision making processes. To successfully grow in their professional roles, teachers should pursue professional learning aligned to their situational needs and with what they value in their practice, alongside school-wide collective

aims.

Teacher agency has been increasingly supported as an influential factor for teacher professional learning, school improvement and sustainable educational change.

Cong-Lem, 2021, p718.

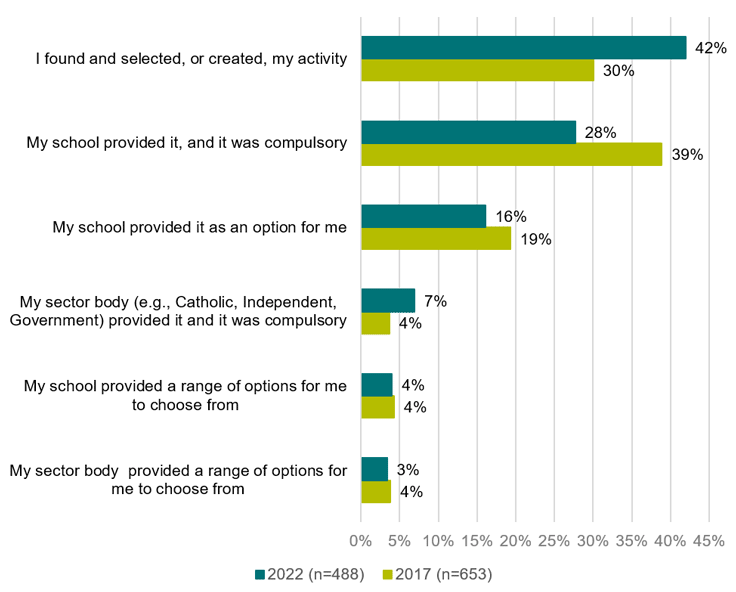

In AITSL’s HQPL 2022 and 2017 surveys, teachers were asked about their role in selecting their most recent professional learning activity. There was a noticeable shift from schools providing compulsory professional learning, to teachers selecting,

or creating, their own learning opportunities. In 2022, 42% of teachers reported selecting or creating their own professional learning activity (n=188) compared to only 30% in in 2017 (n=196) (Figure 6).

Despite this shift, 28% of teachers (n=124) still reported that their school provided compulsory professional learning. Compulsory professional learning occurs for a variety of reasons, including to implement whole-school improvement plans, to keep

staff current with curriculum updates, to assist staff with meeting regulatory requirements (e.g., maintain registration) and to foster a culture of continuous improvement. School systems, sectors and teacher regulatory authorities also play critical

roles in promoting and facilitating whole-school professional learning activities. These bodies develop policies, guidelines and procedures, particularly around teacher and student welfare, and support school leaders to develop positive and supportive

professional learning cultures.

Figure 6. Who is responsible for selecting professional learning for teachers?

There is now a greater focus on what the teacher wants to have their professional learning focus on

Principal, secondary school in Victoria.

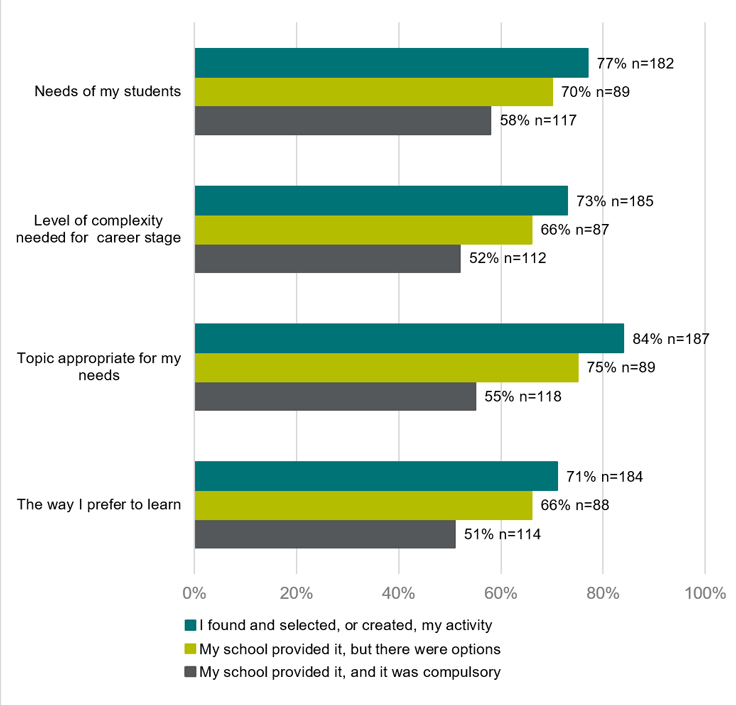

Teacher agency influences perceptions of professional learning experiences

AITSL’s HQPL 2022 survey results indicate that when teachers sourced their own learning opportunities, they were most likely to report that the professional learning better met the needs of their students (77% teacher selected vs 58% compulsory);

was tailored to their career stage (73% teacher selected vs 52% compulsory); covered appropriate topics (84% teacher selected vs 55% compulsory) and offered a preferred mode of learning (71% teacher selected vs 51% compulsory) (Figure 7).

When schools provide professional learning options, teachers tended to have more positive perceptions than when activities were compulsory (Figure 7). These findings suggest that giving teachers more agency in their professional development choices

can lead to more meaningful and effective learning experiences. However, the balance between teacher agency with addressing schoolwide initiatives is very important. When teachers connect their own learning goals with their school’s goals,

it can foster a collaborative environment with shared purpose (Darling-Hammond et al., 2017).

Figure 7. How well professional learning activities meet learning needs

School leaders should value teacher agency and encourage ongoing conversations around professional development opportunities. When teachers are involved in their professional learning choices, they better invest in their learning (intrinsic motivation)

and are more likely to actively shape the learning culture within their school (Cong-Lem, 2021, Kennedy, 2014). Participation in professional learning that positively impacts the professional growth of teachers increases job satisfaction and is

critical for long-term retention of teachers (OECD, 2019). Professional learning is more effective when teachers are engaged and involved. School leaders can balance teacher autonomy, while driving whole-school change and unified approaches to

professional learning using a variety of approaches:

- Clearly communicate school visions and priority areas: Explain the purpose and desired outcomes of whole-school professional learning activities.

- Provide opportunities for teachers to set their own goals and take ownership of their professional learning: This can include allowing teachers to investigate professional learning opportunities and providing resources and support for teachers

to pursue their own learning interests.

- Encourage collaboration and shared decision making: Schools can create opportunities for teachers to work together, share ideas, and make decisions as a team. This can help foster a sense of community and shared accountability.

- Provide ongoing support and resources: Schools can provide teachers with the support and resources they need to implement new strategies and techniques in the classroom, and to reflect on their practice.

- Recognise and value teacher expertise: Schools can acknowledge and respect the knowledge and skills that teachers bring to their roles and provide opportunities for teachers to share their expertise with colleagues.

- Allow teachers to have a voice in school decision making: Schools can empower teachers by including them in decision making processes about school priorities.

- Offer flexibility and autonomy in the classroom: Schools can provide teachers with the flexibility and autonomy to influence decisions about curriculum, instruction, and assessment, and to experiment with different teaching approaches. This will

help teachers feel more invested in the learning process and more in control of their professional growth.

The Australian Professional Standards for Teachers (Teacher Standards) provide a framework for teachers to undertake career stage-appropriate self-reflection and self-assessment (AITSL, 2011). Capacity to think consciously about oneself and one’s

actions allows for self-reflection and self-assessment, practices that have long been considered hallmarks of successful educators (Dewey, 1933). Reflective practice affords continual learning for pedagogical improvement, through meaningful self-inquiry

of one’s own competencies and situational context. The contextualised nature of education means that implementing certain pedagogical approaches is not always replicable. Teachers are therefore continuously moving between practice and reflection,

with each situational context becoming “just a historical moment within a process of permanent change” (Werner Fricke in Wicks et al., 2008).

It is always changing, self-evaluating practice, implementation of new curriculum, students, assessments. It is ongoing.

Teacher, primary school in New South Wales.

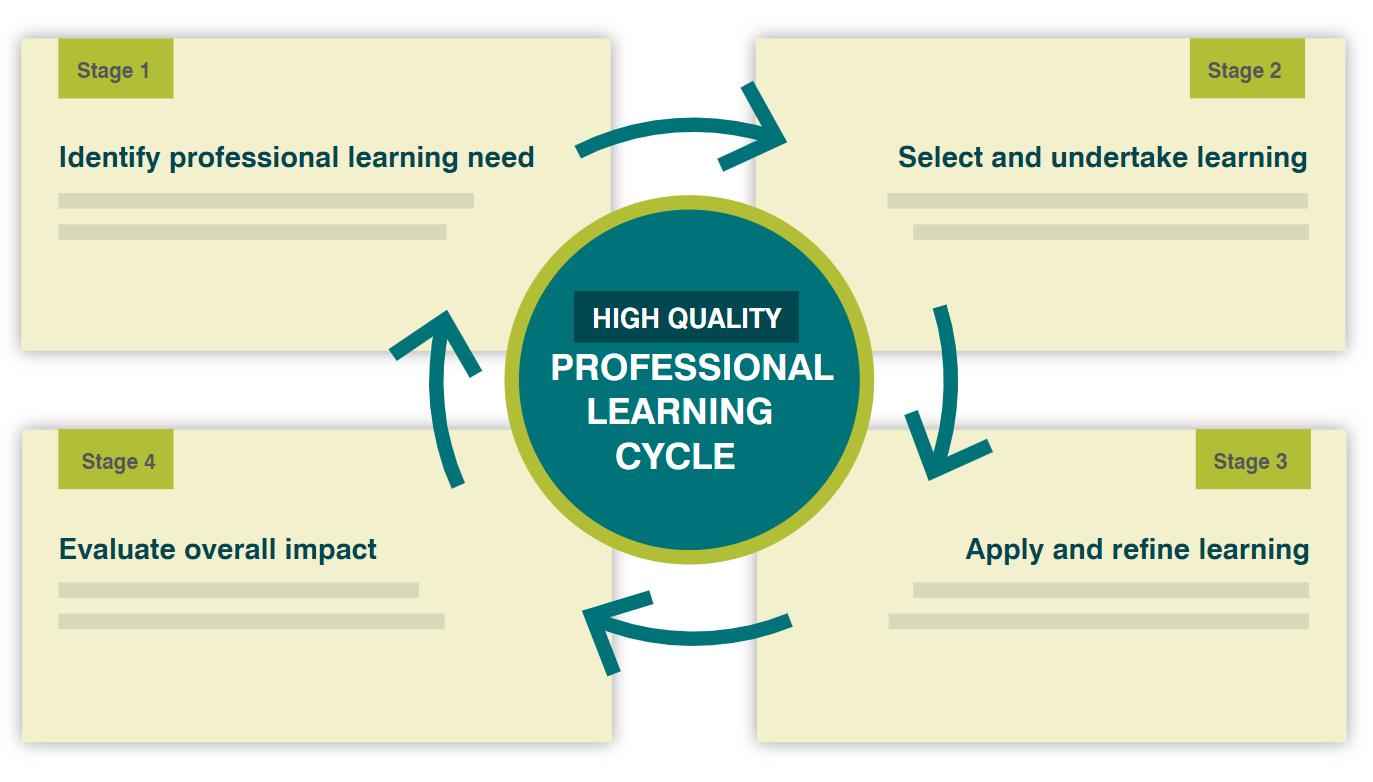

HQPL can be described as an inquiry cycle or action research process; an iterative process of identifying learning needs, undertaking professional learning, implementing that professional learning, and assessing impact (Figure 8) (AITSL, 2020a). AITSL’s

HQPL cycle is underpinned by reflective practice and deepens the teaching-learning process, facilitates continuous professional development, and can assist teachers and school leaders in undertaking professional learning that suits their contextual

needs. Importantly, it anchors reflection in evaluation of the impact of professional learning, using this to inform the selection of future professional learning activities.

Figure 8. Reflective practice through a continuous learning cycle

Professional standards guide HQPL

The Teacher Standards are used to progressively guide whole teaching practice and HQPL, making explicit the elements of effective 21st century pedagogy that elevate educational outcomes.

‘Engage in professional learning’ is itself one of the seven Standards. The Teacher Standards inform the inquiry cycle, serving to benchmark teacher competencies and learning progression. When underpinning collaborative school goals

and group professional learning, the Teacher Standards support teachers to improve their teaching-learning process while concurrently developing the wider organisation. School leaders address a distinct set of professional standards (the Principal Standard ) to guide their own professional learning pathway. The suite of professional standards help guide reflective practice and the setting of professional learning goals.

Educators evidence meeting professional standards for periodic renewal of their teacher registration and when attaining further certification (e.g., Highly Accomplished or Lead Teacher).

It is therefore important for teachers and school leaders that professional learning activities are intentionally and clearly aligned to the relevant professional standards. According to AITSL’s HQPL 2022 survey, most teachers and middle

leaders indicated that the Teacher Standards were either explicitly (49%, n=322) or somewhat (41%, n=269) aligned to their professional learning activities. Providers of professional learning and school leaders should carefully ensure that links

between learning goals, learning activities and the Teacher Standards are made explicit.

Along with supporting teacher involvement in professional learning directions, research highlights the need for educational leaders to create conditions for effective professional learning for teachers. These include:

- ongoing support from leaders or expert teachers

- targeted alignment to existing goals and structures of the educational setting

- flexible delivery of professional learning; and

- understanding readiness to learn (AITSL, 2020a).

School leaders play a crucial role in building a professional growth culture in school communities. Leaders are responsible for creating an environment that empowers teachers to continuously improve pedagogical practice to enhance student outcomes.

Providing opportunities for professional learning, modelling a growth mindset, affording teacher agency, and recognising and rewarding excellence in teaching, are all leader behaviours that can foster the development of HQPL cultures within schools.

Additionally, leaders must lead by example, by continuously growing and developing themselves, guided by the Principal Standard.

Professional learning experiences of school leaders

In AITSL’s HQPL 2022 survey, school leaders (n=130) were asked about their professional learning experiences and environments. Overwhelmingly, school leaders reported participating in five or more separate professional learning activities over

the past year (74%, n=96), spending on average 10.8 hours (n=121, SD=12.73) on their most recent activity. These figures are marginally higher than reported by teachers (60%, 9.8hr) and middle leaders (69%, 9.1hr). This is consistent with findings

from Australian Teacher Workforce Data (ATWD) that the volume of professional learning undertaken by educators increases with seniority (AITSL, 2021). Like teachers, school leaders (n=130) reported online learning as their main type of professional

learning activity (92%), followed by participating in a network conversation (82%) then professional conversations (78%) and general reading (77%).

School leaders and HQPL cultures

Meetings between school leaders and teachers contribute to a positive and collaborative professional culture in schools. These meetings facilitate identifying teacher professional learning needs and provide teachers with opportunities to share professional

growth goals. Additionally, school leaders can align teacher professional learning with school objectives, ensuring that resources and time invested contribute to the overall success of the school.

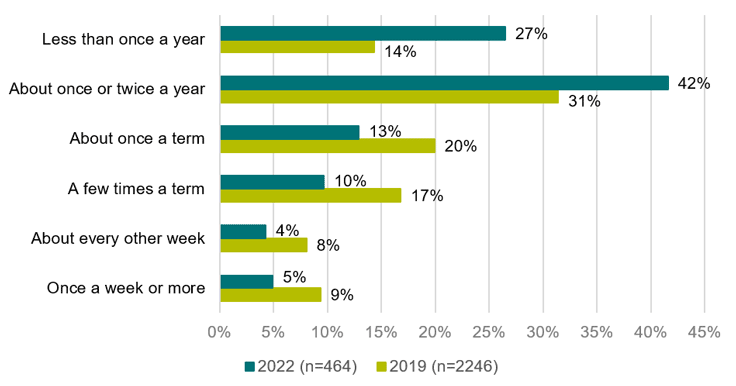

In AITSL’s HQPL 2022 and 2017 surveys, teachers were asked how often they meet with their relevant school leader, including supervising teachers, to discuss development needs and goals (either formally or informally). In 2022, teachers reported

communicating less often with their supervising school leaders than when surveyed in 2017. Most teachers surveyed in 2022 reported meeting their school leader either once or twice a year (42%), or less than once a year (27%) (Figure 9). Whereas

most teachers in 2017 reported either once or twice a year (31%), or about once a term (20%). Given the importance of discussing professional learning goals and planning for professional learning needs, these changes from 2017 to 2022 are somewhat

concerning. Conceivably, the pandemic and current staffing shortages may have contributed to these declines.

Figure 9. How often teachers meet with relevant school leaders to discuss professional learning

Successful educators are lifelong learners, who are reflective and adaptable to current and future learning needs. Educators nationwide have revealed their unwavering commitment towards continuously developing professional knowledge and practice for

improving student outcomes. Our teachers and school leaders together shouldered the brunt of the pandemic, embracing alternative modes of professional learning (e.g., online) for their continued professional growth. Digitalisation has accelerated

and now continues to curtail traditional face-to-face professional learning courses. Regardless of mode, to be genuinely effective professional learning should be relevant, collaborative and future-focused, and based on a strong foundation of

reflective practice that is guided by the Teacher and Principal Standards.

Australia’s educators actively participate in professional learning for personal and professional growth, and for tangible improvements in the quality of teaching. Their principled motivations towards professional learning are commendable. Across

Australia, teachers and school leaders are heavily invested in professional development for improving student learning, engagement, and wellbeing.

Teachers are embracing more autonomy to shape their professional growth and learning environment. However, there seemingly exists a paradox between teachers gaining much needed agency, yet now collaborating less with colleagues and meeting less with

school leaders. These should not be mutually exclusive. Professional learning will be most effective when situated within a HQPL culture underpinned by collaborative practices, connecting teachers and school leaders to colleagues within and across

schools. AITSL has developed evidence-based tools and resources to help teachers and school leaders continue to cultivate HQPL cultures (see Resource list). Some have been highlighted throughout this Spotlight.

Footnotes

- There were 474 teachers (60%), 192 middle leaders (24%), 74 deputy principals (9%) and 56 principals (7%). It was not compulsory for respondents to answer every question, therefore the number of responses received for each question varies. 714 survey respondents completed the survey in full. It is worth noting that there are statistical constraints on the conclusions drawn due to the sample size of AITSL’s survey.

- Percentage and respondent number (n) refer to the proportion of participants who answered a given question. Not all participants answered all questions.

- Standard deviation (SD) indicates, on average, how far each value within the given dataset lies from the mean.

ACARA. (2018a). Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Capability (Version 8.4). Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA). https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/f-10-curriculum/general-capabilities/information-and-communication-technology-ict-capability/

ACARA. (2018b). Student diversity. Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA). https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/resources/student-diversity/

AITSL. (2011). Australian Professional Standards for Teachers. The Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL). https://www.aitsl.edu.au/docs/default-source/national-policy-framework/australian-professional-standards-for-teachers.pdf

AITSL. (2017a). Become a registered teacher. https://www.aitsl.edu.au/prepare-to-be-a-teacher/become-a-registered-teacher

AITSL. (2017b). Build a professional growth culture. The Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL). https://www.aitsl.edu.au/lead-develop/develop-others/build-a-professional-growth-culture

AITSL. (2017c). Uncovering the current state of professional learning for teachers: Summary findings report. https://www.aitsl.edu.au/docs/default-source/hqpl/aitsl-hqpl-summary-findings-report-final.pdf

AITSL. (2018). Australian Charter for the Professional Learning of Teachers and School Leaders. https://www.aitsl.edu.au/docs/default-source/national-policy-framework/australian-charter-for-the-professional-learning-of-teachers-and-school-leaders.pdf?sfvrsn=6f7eff3c_8

AITSL. (2020a). Practical Guide – Inquiry Cycles. The Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL). https://www.aitsl.edu.au/teach/improve-practice/practical-guides/inquiry-cycles

AITSL. (2020b). The role of school leadership in challenging times - Spotlight. https://www.aitsl.edu.au/research/spotlights/the-role-of-school-leadership-in-challenging-times

AITSL. (2021). Australian Teacher Workforce Data (ATWD). https://www.aitsl.edu.au/research/australian-teacher-workforce-data/key-metrics-dashboard

Brook, L., Sawyer, E., & Rimm-Kaufman, S. (2007). Teacher collaboration in the context of the Responsive Classroom approach. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 13(3), 211–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540600701299767

Cole, P. (2012). Linking effective professional learning with effective teaching practice. https://ptrconsulting.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/linking_effective_professional_learning_with_effective_teaching_practice_-_cole.pdf

Cong-Lem, N. (2021). Teacher agency: A systematic review of international literature. Issues in Educational Research, 3, 718–738. http://www.iier.org.au/iier31/cong-lem.pdf

Darling-Hammond, L., Hyler, M. E., Gardner, M. (2017). Effective Teacher Professional Development. Learning Policy Institute. https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/sites/default/files/product-files/Effective_Teacher_Professional_Development_REPORT.pdf

Dewey, J. (1933). How we think: a restatement of the relation of reflective thinking to the educative process. D.C. Heath.

Heffernan, A., Magyar, B., Bright, D., & Longmuir, F. (2021). The Impact of COVID-19 on Perceptions of Australian Schooling. https://www.monash.edu/education/research/downloads/Impact-of-covid19-on-perceptions-of-Australian-schooling.pdf

Kennedy, A. (2014). Models of Continuing Professional Development: A framework for analysis. Professional Development in Education, 40, 336–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2014.929293

Lay, C. D., Allman, B., Cutri, R. M., & Kimmons, R. (2020). Examining a Decade of Research in Online Teacher Professional Development. In Frontiers in Education (Vol. 5). Frontiers Media S.A. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2020.573129

Masters, J. (2018). Trends in the Digitalization of K-12 Schools: The Australian Perspective. Seminar.Net - International Journal of Media, Technology and Lifelong Learning, 14(2), 120–131.

NEiTA–ACE. (2021). Teachers Report Card 2021: Teachers’ perceptions of education and their profession. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1HrzGkDKnRLgklW3vLY4otrpctmPZ5jbX/view

OECD. (2014). TALIS 2013 Results: An International Perspective on Teaching and Learning. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/talis-2013-results_9789264196261-en

OECD. (2019). TALIS 2018 Results (Volume I): Teachers and School Leaders as Lifelong Learners. https://www.oecd.org/education/talis-2018-results-volume-i-1d0bc92a-en.htm

OECD. (2020). Innovating teachers’ professional learning through digital technologies. https://www.oecd.org/officialdocuments/publicdisplaydocumentpdf/?cote=EDU/WKP(2020)25&docLanguage=En

Wicks, P. G., Reason, P., & Bradbury, H. (2008). Living inquiry: Personal, political and philosophical groundings for action research practice (Vol. 2). The Sage handbook of action research: Participative inquiry and practice.